Celebration of Punjabiat at Kila Raipur

Its the winter sun in Kilaraipur. The audience has started to gather for the annual village olympics event. The girls team is warming up for the hockey match. The horses are being fed for the race ahead. The tractor tires are being cleaned up for the tractor tyre race. The screeching of mic is starting as the audio is being setup. And men (its all men) from the nearby villages are starting to stream in to catch some live sporting action.

This is the sort of sporting action that won’t make it to the Olympics anytime soon.

The hockey ball rolls past me from a practice session of the girls hockey team. The echo of their sharp hits is echoing across the stadium as they warm up. They are focused and oblivious to all the chaos around them. The whistle goes off, the the match is on. The quality of skill and aggression is high. These girls are the only female presence at the entire event. Sports is a gateway to breaking out of the social norms that many women may feel locked in, and probably find a better life, and even a job.

The tyre company sponsoring the race has a tractor tyre race included in the competition, and the sanitary pad company has integrated their sanitary pads into the women relayrace – as batons! The primary financial support for the festival is the patronage of the NRIs. There are constant shoutouts of contributors and their countries – USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand – which are only briefly interrupted for the hockey updates. It feels like a subtle brainwashing, perpetuating the belief in the local youth that these countries are overflowing with wealth and opportunities.

A parasailing showcase event takes off. The big propeller behind the pilot pushes the para-sail into the sky. He floats precariously over the field where the hockey match is going on, before catching the wind and finding a safer altitude. A flag flittering behind him carries his phone number for people to contact him. Below him an old man just finished a 10 km run, which no one paid attention to, but he manages to convince the TV crew to interview him.

As the day progresses the contests and skills start to get into a stranger zone.

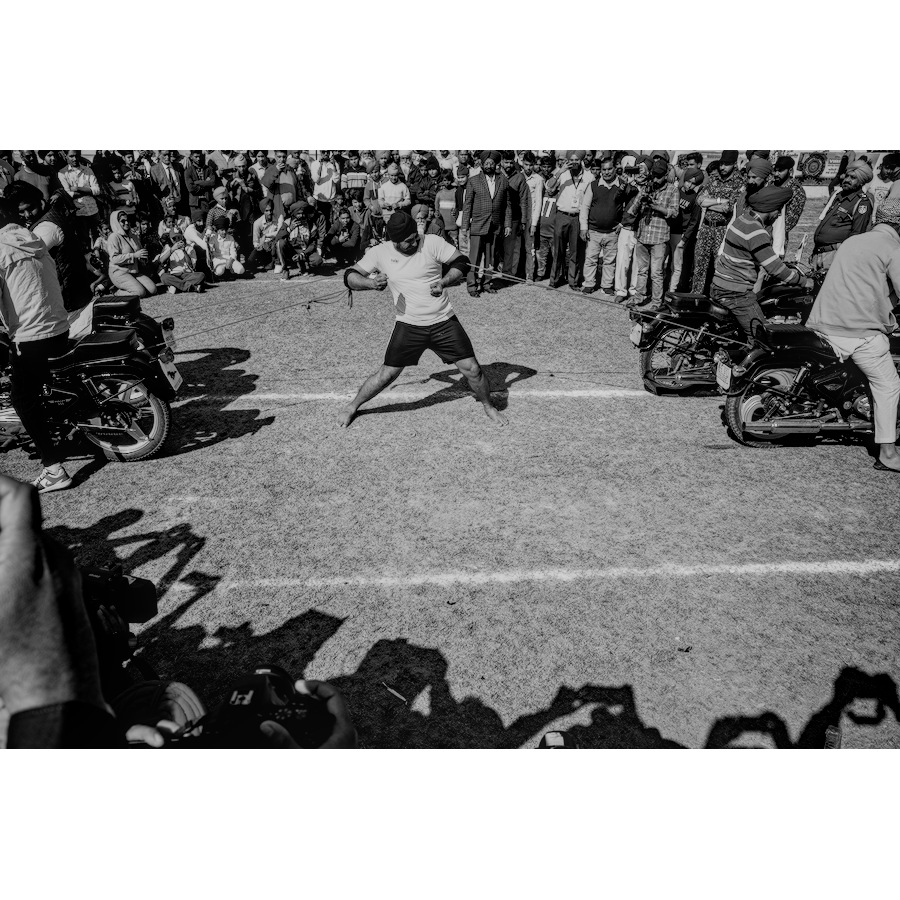

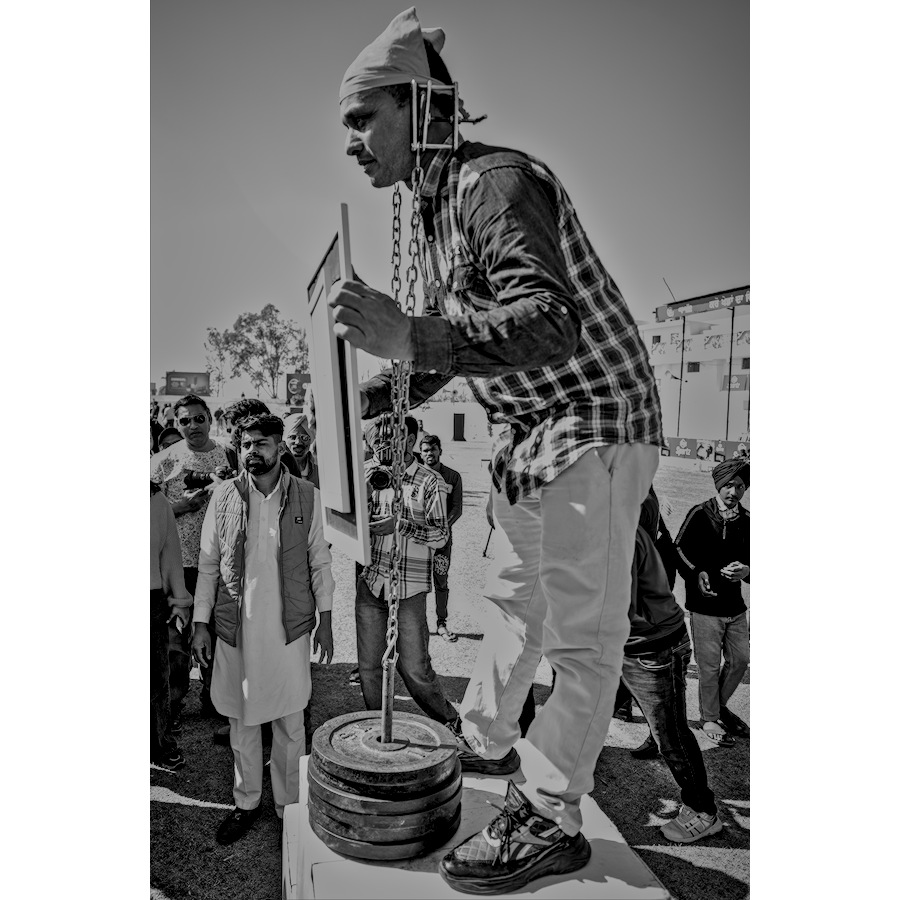

A guy shows off his strength, by pulling a car with his teeth. Another lifts heavy weights with his ears. One old man shows that he still has the power, and can lift a heavy gunny sack on his back. There is another old man who shows he can do a headstand for a long time. A young guy holds four bullets bikes (250cc each) with is hands pulling them back against acceleration. All of them get an official prize money of Rs500 for their pains. But they all then walk around the ground, topping that prize money up from the generosity of the by-standers.

The men Kabbadi session starts, which is the main event. The men are rippling bundle of muscles. Every player is sporting a fresh haircut and is wrapped in enough bandages to be cast in some Zombie movie.

For them the prestige of winning is more important than bodily pain which will probably heal anyway.

The crowd acts as the third umpire weighing in on every dispute of the boundary. Occasionally these Herculean bodies crash into the audience, but no one complains. An announcement is made to stop the match as some visiting dignitary has arrived and will honour the teams with some medals. The match stops, with no one complaining except for the commentator, who hangs his head in disapproval that his fluid commentary has been interrupted. He seems to have many quotes for kabbadi players for every situation, and never seems to run out of them.

The main attractions aren’t the games and the players, as much as a few of the white-skinned foreigners.

They are the biggest tippers to the athletes, probably embarrassed by the small amounts the winners seem to be getting. They are also part of everyones selfies. Some of the demonstrations are redone, or rescheduled so they can witness it as well. The shrill American accent is as loud as the blaring announcement on the speakers. They seem to assume that the games are organised in their honour, with people around them giving enough reasons to believe it too.

The Nihang warriors have had enough waiting for their turn to showcase their skills, and decide to leave. There is some confusion if they can just get up and leave, but they are clear that they are the ones who decide.

As we drive away from the village, we reflect on the surreal day we had just experienced. This is a land of martyrs, where religion and self-defence are intertwined. This festival, which started in 1933, is a celebration of all that is Punjabiat – where physical prowess is revered, as much as humility and big-heartedness. It has become a festival where culture and sports have merged into this unique format, which is ripe for someone to help take it into a bigger league.